Introducing Git

- Author: Néhémie Strupler

- Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0

Table of Contents

- Git: an overview

- Why use Git in an archaeological project?

- GitLab, a hub for Git

- Some online resources

- References

- Notes

Git: an overview

Git is a “free and open source distributed version control system”[1]. The aim of a version control system (short VCS, also called ‘revision control system’) is to track snapshots of the changes made to files inside a folder. Originally it was designed to help coders, but can be used to track any type of file. This tracking system can be used standalone, but is particularly useful for facilitating the simultaneous or parallel work between multiple authors.

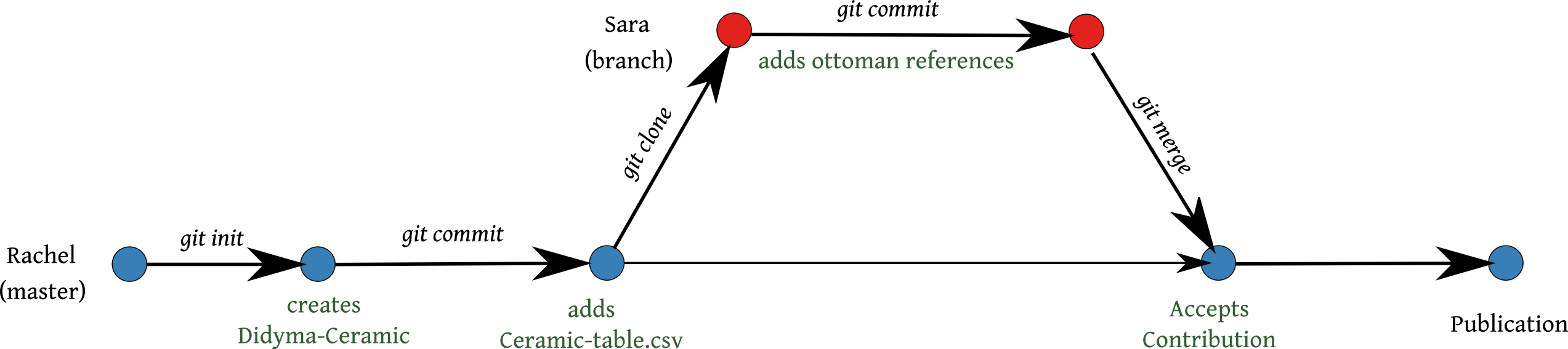

Let’s start with an example:

Rachel[2] decides to start a project about an assemblage of ceramics found near Didyma.

She makes a new folder on her computer and calls it “Didyma-Ceramic”.

With Git (either using the command line or a graphical interface) she transforms her folder into a git repository (git init).

Now, every snapshot made inside this folder is tracked (a snapshot, called in 'git-language’ a commit’, saves the state of the project)[3].

She creates a first table, called “Ceramic-table.csv”, using her normal table software, with all the information she could find in the literature and saves her changes with a snapshot (git commit).

During her research at the library, she meets Sara, a specialist on the Ottoman period.

Sara decides to collaborate with Rachel and clones (i.e. makes a copy of) the “Didyma-Ceramic” repository (git clone).

Sara edits her copy of the table “Ceramic-table.csv” with references from Ottoman literature that Rachel couldn’t read (Ottoman is a very hard language, much harder than Git).

As soon as she finishes her work, Sara commits her copy of the table (i.e. saves a snapshot in her “Didyma-Ceramic” repository) (git commit).

Now Sara’s repository contains her changes and the initial table of Rachel, knitted together.

Git tracked the time of the changes and assigned the name of the author to each line of the table.

Rachel and Sara know that their work is attached with their name.

Sara sends her changes to Rachel by pushing her copy back to Rachel’s computer or a shared central server (git push).

When Rachel sees the changes, she is really happy and merges Sara’s changes into her repository (git merge).

A month later, Rachel finishes her work and wants to publish her results. With the help of Git it is now really easy to acknowledge the work of Sara. She is proud to make her work more transparent for the scientific community and to recognise the contribution of Sara, as the ethics of science expect.

Why use Git in an archaeological project?

Archaeological projects and surveys are rarely very transparent about the creation of their data. Most of the time, collecting is a team effort, but team members are mostly only acknowledged in a side note “We would like to thank Sara and Rachel for their work during the campaign at Panormos in 2015”.

Today as collection of archaeological data becomes increasingly digital, Git offers work-flows to move towards more transparency in the collection and the authorship of the data (Ram 2013). Initially Git was created by Linus Torvalds for the “Linux Kernel” Project. The aim of Git was thus to enable the collaboration of hundreds of developers on the same project. 'Developers’ can, of course, be any kind of author. This section therefore presents a quick overview on some aspects of the software we consider the most relevant for 'developers’ and 'authors’ on an archaeological project.

Tracking authorship

Git is a master for tracking authorship. The software is a version control system and a message from a specific contributor is attributed to each committed changes (“Adding new pottery from Ottoman literature”) with an author (“Sara”). Each committed change (i.e. snapshot) is kept in the repository’s history and under normal circumstances should never be deleted[4], allowing the development of the data to be reviewed later. The power of Git can be best leveraged by using plain-text formats (e.g. .txt, .csv, .xml, .gml). Using these “simple” and open formats allows Git to scan the content and to highlights sections that have changed. In this case, each line is attributed to a specific author.

This tracked authorship is similar to Microsoft Word’s or Libre Office’s tracking changes. But, with Git committed changes are never lost and are stored in the history. Even if someone changes just one word in a file, her/his name will be associate with the relevant line[5].

Collaborating

Git is a decentralized and distributed VCS.

That means that each collaborator keeps a complete copy of the data and history that can be used as server or as client.

A complete copy of the repository makes working off-line possible. On synchronising (pushing) only updates made to the local copy are uploaded, reducing the amount of network traffic.

Git provides a branching mechanism that makes it easy for exploring ideas, experimenting with files and enables contributions to be managed.

By default there is a master branch, this is the central flow of a project.

Development is often made on a second branch (in our case drafts or develop) so that changes can be reviewed before they are incorporated into the master.

Only approved changes are merged by the administrators (in the story above, Rachel could have refused Sara’s changes).

Git enables fine-grained control of the project, by defining branches and appropriate rights for those different branches.

To visually explore the branch system of Git, its “killer feature”, go to the website Learn Git Branching

Reproducibility

The growing rate of retraction of academic paper in the last ten years has been accompanied by a spreading movement advocating stronger reproducibility in science. “Reproducible science provides the critical standard by which published results are judged and central findings are either validated or refuted” (Ram 2013). Since the birth of computational research and analysis, only the 'best’ (i.e. positive) results tend to get published, and failed procedures or negative results remain forgotten and unpublished. Reproducibility is the idea that everyone can start from the collected data and apply the same set of procedures to verify the results. Alongside other open source technologies, Git makes it easier to follow better and more robust science practices again, by providing a way to track the transformations of the data made by the authors.

By achieving more openness (providing raw data, tracking changes, …) Git lowers the barrier for data reuse. For empirical research like archaeology, it facilitates merging different data-sets or reusing the same data-set for answering new questions.

Archiving the data

Archiving digital data is directly linked to reproducibility. Working in a distributive collaborating environment drives users to apply good practices in curating digital data. As everyone contributes within the same system Git encourages authors to be explicit about the structure and format of the data-set and encourages researchers to choose “extended-life file format” by avoiding binary and proprietary formats.

Git uses a simple repository format that doesn’t modify the data itself. Even if the world has forgotten about Git in the future, the final files will remain accessible.

GitLab, a hub for Git

Interaction with Git is mainly done with the command line [6]. As it’s not very intuitive for many, web hosted service, like GitLab or GitHub, can also be used to make Git easier and for providing a central origin for sharing the repository between collaborators. That’s why we are using GitLab for supporting the work with Git. Go to the GitLab handbook file to learn how to contribute!

Some online resources

- Pro Git Book with a nice video-section

- Basic Git commands

- tryGit

- Learn Git Branching

References

Ram, Karthik. 2013. “Git Can Facilitate Greater Reproducibility and Increased Transparency in Science.” Source Code for Biology and Medicine 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1751-0473-8-7.

Notes

[1]: Home-page from the Pro Git Book. Accessed 2015.07.15

[2]: Rachel and Sara are fictional characters, but willing to play in this fiction. As in all fairy tales, this story simplifies the process a little for clarity of story line

[3]: Changes made to files between 'commits’ (snapshots) can be locally saved but are not tracked, however. All files are effectively treated as drafts until a commit is made as far as the repository is concerned.

[4]: Deforming history is evil and dangerous.

[5]: This principle is not without drawbacks and the statistics provided on “amount of contribution”, like any kind of metric, lacks details, notably as deleting is never (positively) evaluated. Dummy quantification is always problematic.

[6]: Alternatively there are some more user-friendly user-interfaces for Git which may be useful for some purposes (e.g. SourceTree), but some of them are not free, and it is still important to understand the underlying mechanism of Git to use them effectively.

panormos/team

panormos/team